Hey kids, want some yummy apps?

The new Stranger Danger for kids and adults. Your apps.

New rule: Don’t take candy (and apps) from strangers.

Like a stranger with candy, you may focus on the yummy candy or the stated “fun” part of the app you just downloaded. But like a danger stranger’s ulterior motives, we may fail to see the true purpose of the app or offer.

We forget apps can walk and chew gum at the same time.

An app is not a product you purchase for a singular function, like a chair. A chair offers one function: a place to sit (okay, holding up and using it for lion taming is the other).

On the other hand, apps consist of code to handle a variety of tasks. The number of task that are solely determined by the ability and the desire of its creator. It can include code where you can write and run a program to allow the user to play a game or see a picture.

At the same time, other code can run within the same app that quietly performs other tasks that may have nothing to do with delivering that game or picture. Like “borrowing” your personal information.

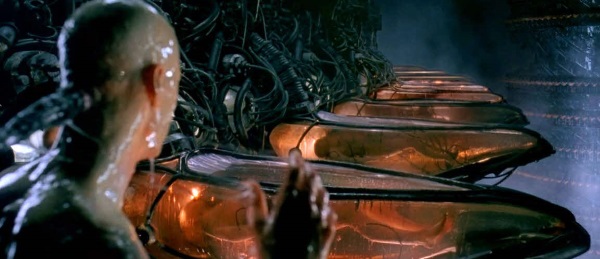

Essentially some apps can be like a Trojan horse.

Software can act like its namesake horse-looking subterfuge. A wooden horse secretly filled with soldiers that the Greeks used to sneak into the city of Troy and win the war.

Most of us with computers previously experienced this as a type of computer virus that hides within software code. Today’s apps don’t pillage your system as much as infect it. In either case, the story is the same: “what you see in an app is not always what you get.”

Safe from malware. Apparently, not mal intentions.

A recent example. Avast, a company that offers free malware protection (I am a user..but not for much longer) was revealed to be sharing information gathered from the computers it was installed on with third parties.

Through its relationship with a division called Jumpshot, Avast used it’s computer security monitoring services to produce and share its harvested user data with clients including Google, Yelp, Microsoft, McKinsey, Pepsi, Sephora, Home Depot, Condé Nast and Intuit.

Some of Avast’s clients paid to gain access to data from its products that were able to track detailed user behavior, clicks, and movement across websites. Some of the data is reported to include:

- URLs visited, in what order and when

- Google searches

- Lookups of locations and GPS coordinates on Google Maps

- People visiting companies’ LinkedIn pages

- YouTube videos

- Videos users are watching on Facebook and Instagram

- People visiting porn websites

For those who downloaded the free security software app (like me), do you really feel secure now?

Swipe right while some apps swipe your privacy.

Think you’re just sharing your profile with “HotG” on dating apps like OkCupid, Tinder, and Grindr? You might be surprised.

Sources, including the New York Times, report that these dating services share user information like dating choices and your location to advertising and marketing organizations. Grindr, a gay dating app, sent user-tracking codes and the app’s name to more than a dozen companies, essentially sharing and even disclosing a user’s sexual orientation without the user consent or knowledge.

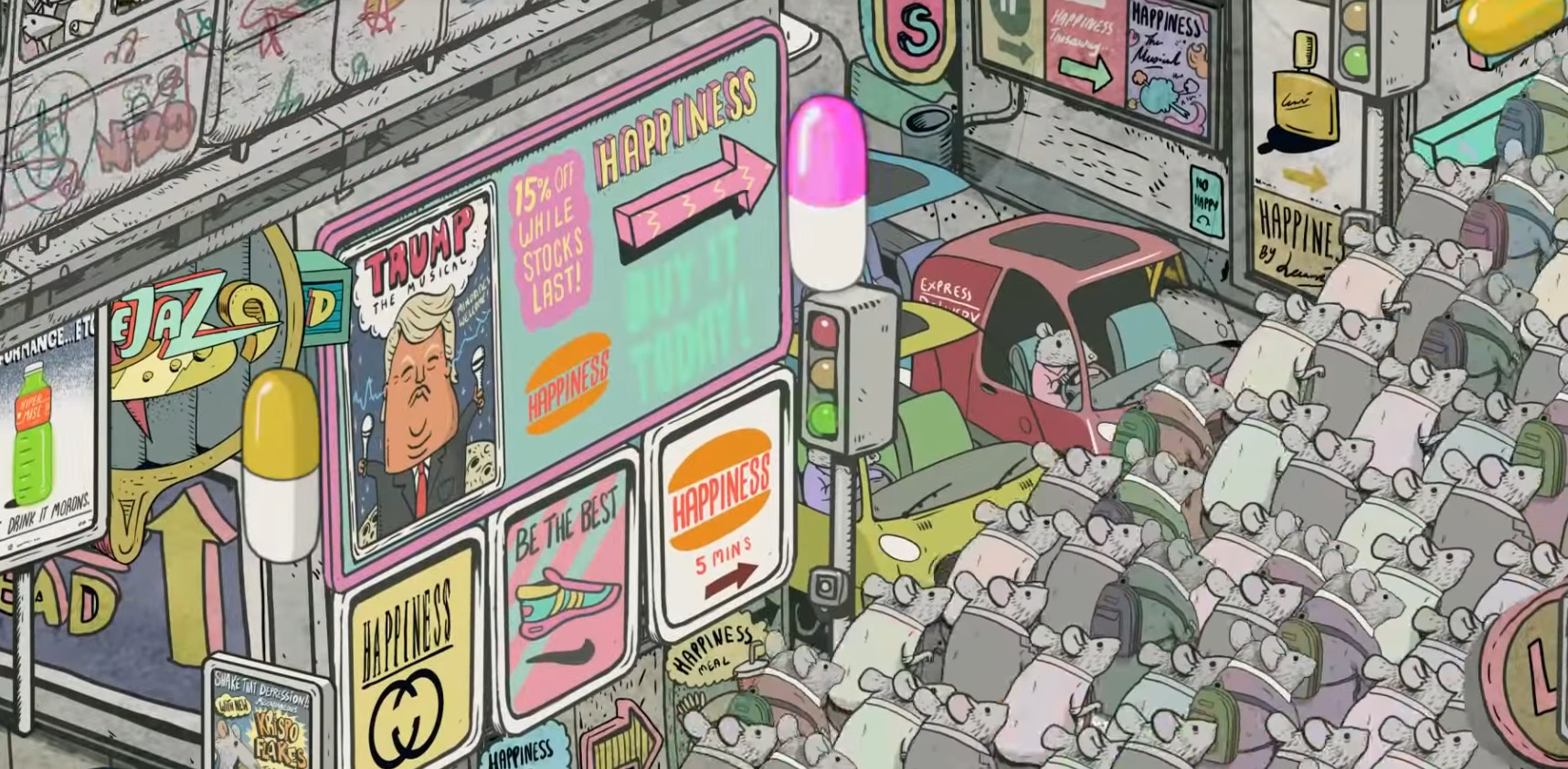

Hmmm. I’m using an app for one service. I’m being used for another. Where have I seen that before….

Ok, ok, extreme. But you get the idea. You need to do a cost benefit analysis to separate your benefit from using an app from the maker’s benefit and gains.

Getting back to Avast. There is an irony about a company offering an application to protect you while secretly sharing sensitive data with people you don’t know so they can learn more about you without your knowledge or control.

Sometimes they do it even when you exert control.

In fact, reports from researchers revealed that more than 1,000 Android apps harvest your data, even when you expressed for them not to.

Apps that are not given permission by users are still able to leech and capture the data they want via other apps that do have permission to your data. According to the researchers, these apps can gather data from your Wi-Fi connections as well.

How can you tell if apps are working behind your back?

Are you having a deja vu feeling as you start seeing ads on apps or in your browser for items you looked up in a completely different app? You might be witnessing the apps slurping up data from your phone or device.

Sleeping? Data harvesters are just getting to work.

While your data may be collected during the day, it often continues even while your phone is at your bedside and you are asleep.

A very eye-opening example.

A reporter, Geoffrey A. Fowler for the Washington Post, used software to track the activity of apps on his smartphone. He learned that some of the apps he was using were sending data from his phone to business and companies, including some firms he didn’t recognize.

Some excerpts from the article of what he found in his reporting:

“On a recent Monday night, a dozen marketing companies, research firms, and other personal data guzzlers got reports from my iPhone.

At 11.43 pm, a company called Amplitude learned my phone number, e-mail, and exact location.

At 3.58 am, another called Appboy got a digital fingerprint of my phone.

At 6.25 am, a tracker called Demdex received a way to identify my phone and sent back a list of other trackers to pair up with.

And all night long, there was some startling behavior by a household name: Yelp. It was receiving a message that included my IP address.

But we’ve got a giant blind spot when it comes to the data companies probing our phones.

iPhone apps I discovered tracking me by passing information to third parties – just while I was asleep – include Microsoft’s OneDrive, Intuit’s Mint, Nike, Spotify, The Washington Post and IBM’s The Weather Channel. One app, the crime-alert service Citizen, shared personally identifiable information, in violation of its published privacy policy.”

Creepy is an unauthorized attempt for intimacy. This is creepy.

It is a bit disturbing that apps not only ignore or bypass your privacy settings but then robustly share your data on your phone with people you don’t even know.

Why is this no different than someone sneaking through my house when I’m asleep, rifling through my papers and files and then sell that info to a third party? It’s not.

And I’ll just take a moment to remind you, your kids probably have smartphones, too.

Then the next question, why isn’t anyone doing anything about this digital “Danger Stranger?”

Probably because there are clauses in the Terms and Conditions for these apps that make it hard for me or any of you to take significant action.

Steps to help users fight stranger danger.

To Facebook’s credit, it recently introduced a “clear history” button at the top of the page. The new feature will allow users to erase all the off-Facebook data presented. You can also click on each app or website in the list to see how much data they’ve shared and stop them from doing so.

Make no mistake, this visibility can give users greater control over how their data is used. Control that can hurt the financial model Facebook and app partners rely on.

So why offer the service? Executives, off the record, give away the game. They offer such features, not just for the upside of PR, but because they are betting that consumers don’t care enough about access to their data to use it.

What did I do?

I recently downloaded Jumbo, a privacy app for iOS. It is a “privacy assistant” that helps to tell me what happens with data and helps manage my privacy settings across platforms like Google, Facebook and Twitter. You can learn more about Jumbo here.

Something like this is not perfect, but it’s a start. Hopefully the start of more conversation and cynicism about just downloading apps simply because they are offered to us, mostly for free. We must not just think about how the app might satisfy our needs, but what is the true end-game for the app.

The bigger task is for all of us to ask questions about apps before we download them to our phones.